Is Intranasal Ketamine Safe and Effective for the Treatment of Depression?

Standard prescription antidepressant medications are poorly effective at best, and come with a host of potential side effects. As such, it’s not surprising that the pharmaceutical industry is looking for additional options.

Recently, ketamine has been found to have short-term, fast-acting antidepressant effects. In the original research, ketamine was administered intravenously, making ketamine treatment somewhat unwieldy. The first study of intravenous ketamine as a treatment for depression was published in 2000 (Berman 2000). Additional trials of intravenous ketamine followed, with the majority confirming short-term, fast-acting benefits for improving mood (Rot 2010).

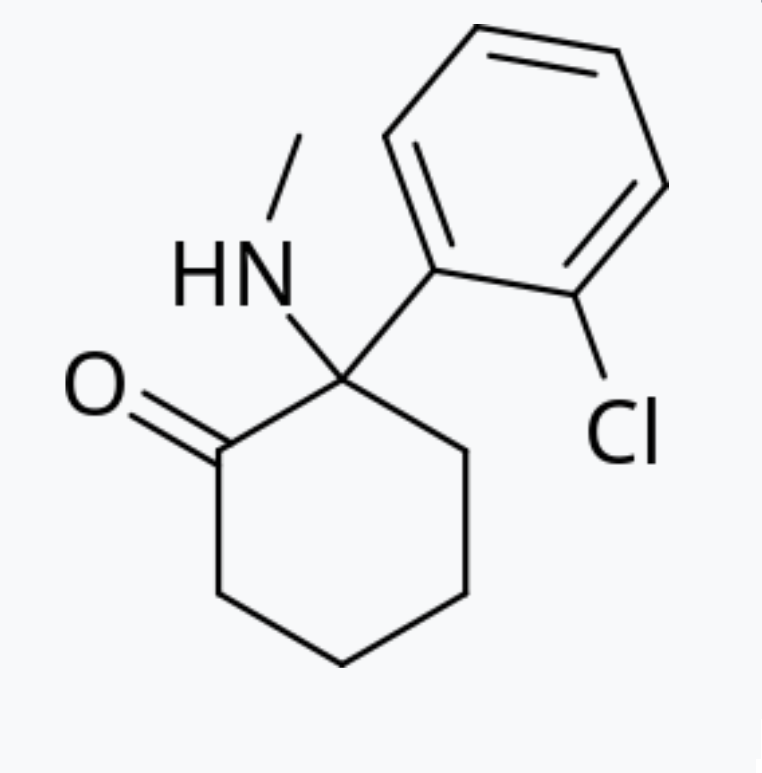

As a drug, ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic, often used in veterinary medicine to put animals under for surgery. Beyond its anesthetic effects, ketamine acts on the glutamate neurotransmitter system. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter. In other words, it speeds up brain activity. Data suggests that excess glutamate may be involved in a number of different mental health conditions, including depression (Sarawagi 2021). However, ketamine is also a common street drug that people abuse due to its hallucinogenic properties. The drug isn’t without risks, as regular use can lead to kidney damage, spikes in blood pressure, cognitive impairment, worsening depression and impaired driving ability (Selby 2008, Morgan 2010, Craven 2007, Ke 2018, Giorgetti 2015).

Intranasal Ketamine and Depression

Initial Studies and Short-Term Treatment Effects

Due to the early success seen with intravenous treatment, Janssen Pharmaceuticals developed a nasal spray version of the drug as a treatment for depression. The drug was approved in 2019 with the official name of Spravato (generic name Esketamine).

The first clinical trial of intranasal ketamine was in patients struggling with treatment-resistant depression already on antidepressant medication (Daly 2018). The study found rapid antidepressant effects of which the authors claimed were somewhat durable for two months. Initially, depression levels decreased more on ketamine treatment than placebo. However, treatment effects were assessed two hours after taking the drug and arguments have been made that these short-term improvements are related to the “high” experienced from ketamine itself. In the study, after two months of treatment, the benefits no longer achieved statistical significance.

The second clinical trial explored the use of intranasal ketamine for improving depression levels in suicidal patients (Canuso 2018). While initial treatment again rapidly decreased depression symptoms, by the end of the 25-day study period, the differences between ketamine and placebo were no longer significant.

A larger study did find that the benefits of combining intranasal ketamine with an antidepressant was better than an antidepressant alone by day 28 (Popova 2019). However, the effect size was modest and side effects were significant in around 25% of patients taking ketamine. The most common side effects were considered mild and included dizziness, dissociation, trouble swallowing, vertigo and nausea.

A similarly sized trial in elderly patients did not find that intranasal ketamine had any significant treatment advantages over antidepressants alone (Ochs-Ross 2020). Similarly, a clinical trial in Japan also did not find significant antidepressant effects over six weeks of treatment with intranasal ketamine (Takahashi 2021). Still other studies suggest that benefits may outweigh risks for depression treatment in the short-term and that ketamine may initially help suicidal patients with major depression (Katz 2021, Ionescu 2021).

Long-Term Treatment Effects

The first long-term trial of intranasal ketamine included 802 patients with a goal of tracking responses over six months to one year in a subset of participants (Wajs 2020). Side effects similar to those reported in the short-term trials occurred in 90% of patients with almost 10% of patients discontinuing ketamine treatment. The study concluded that side effects were manageable and antidepressant effects were sustained, but treatment included ketamine and an oral antidepressant medication with no placebo group. The study was continued for up to four and a half years and claimed to have found continuing benefits. Nevertheless, without a placebo group, it is hard to know the actual real-world benefits.

To better understand long-term outcomes, longer placebo-controlled trials are needed to assess the efficacy of intranasal ketamine for treating depression.

Other Potential Concerns

Based on the available data, other concerns have been raised with ketamine for depression treatment (Horowitz 2021). In the studies submitted for licensing the drug, there were a total of six deaths, three of which were suicides. All of the deaths were in patients receiving ketamine with no deaths reported from placebo. Of the non-suicide deaths, one was a motorcycle accident, one was a heart attack and one was acute heart and lung failure. Due to blood pressure changes and dissociative effects, it’s possible these deaths were related to ketamine even though the study authors tried to conclude that they were not. While some data also suggests ketamine can decrease suicide risks, three deaths in the treatment group from suicide obviously still raises concerns.

Beyond the fatal events, there was a brain bleeding event and five additional non-fatal car accidents in the ketamine treatment group, all of which could have been related to medication-based side effects (Horowitz 2021).

Kidney and bladder problems commonly ocurred, with 20% or participants describing urinary symptoms (Horowitz 2021). Concerningly, over the course of the study, there were reports of cognitive impairment in older individuals. Yet the findings were dismissed by the FDA due to “individual variability,” ignoring the fact that cognitive problems are associated with ketamine abuse.

Conclusion

While a fast-acting antidepressant is a potential boon for modern medicine, it may be wise to slow down in the utilization of ketamine without better, long-term clinical trials that can clearly assess safety, efficacy and risks. It is also worth recognizing that at best, treatment benefits are most likely quite modest, as a number of the short-term trials found no continuing benefits after one month’s treatment.

With the available data, safety concerns for ketamine use do not appear to have been completely resolved. Cognitive impairment, accidents, kidney damage and non-fatal or fatal events related to blood pressure elevations are all still likely of some concern.

Good read! What were the study/sample size for the licensing studies?

The first clinical trial they used was only 60 people. The only clinical trial submitted for approval that showed a benefit included 197 patients that completed the study and only lasted four weeks. The benefits were quite modest. The other studies found the benefits didn’t hold. It’s kind of strange that the drug got approved in the first place with such weak evidence of benefit and potential safety concerns.