Serotonin and Depression

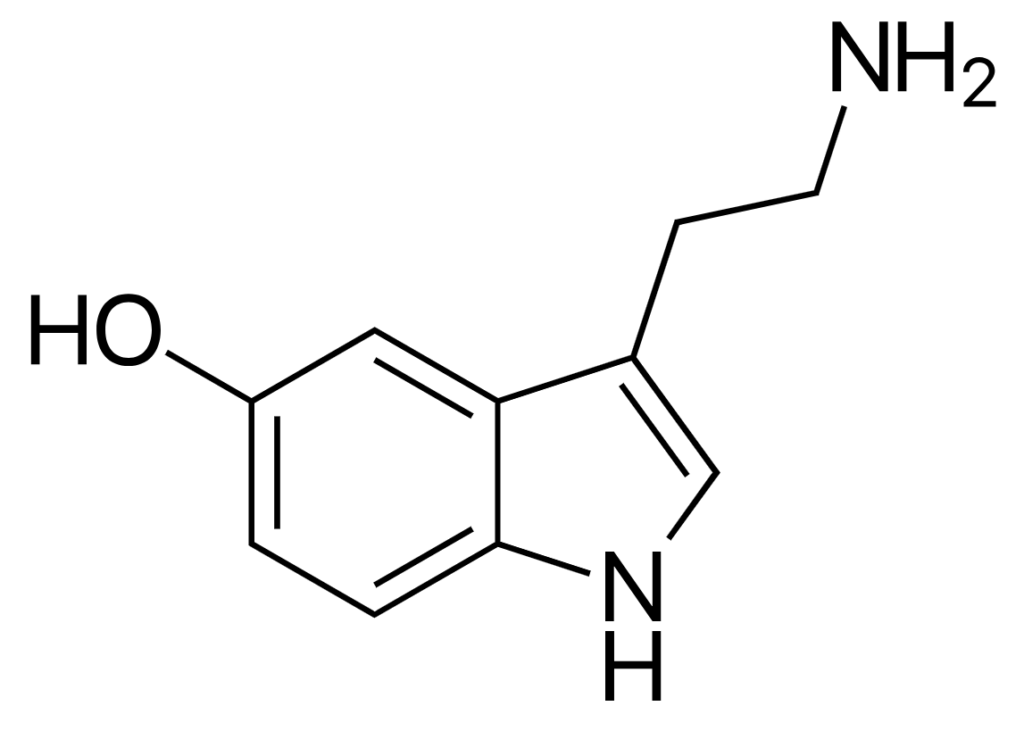

For many years, the pharmaceutical industry has been marketing antidepressant medications as a fix for “chemical imbalances” that underlie the symptoms of depression. The main “chemical” that is thought to underlie depression in the brain is the neurotransmitter serotonin. While it may sound like the serotonin hypothesis of depression is an accepted fact, a lot of the published data is contradictory.

Origins of the Serotonin Hypothesis of Depression

The first drugs that were successful in helping to reduce symptoms of depression were initially poorly understood. Yet due to their effects in patients, researchers attempted to understand their underlying mechanisms. It was noted that the drugs influenced neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that imbalances in neurotransmitters were the cause of depression (Coppen 1967).

This hypothesis was leveraged even further with newer antidepressants that focused mostly on serotonin, starting with Prozac (Cowan 2008). Prozac was thought to work specifically by blocking the reuptake of serotonin. By blocking reuptake, more serotonin is available throughout the brain. This Increased serotonin was thought to reverse deficiencies of the chemical. Yet even with all the marketing and publicity for antidepressant medications, cracks in the serotonin hypothesis were already apparent for anyone willing to question the narrative.

Problems with the Serotonin Hypothesis

Medication Onset

One of the most glaring problems with the serotonin hypothesis is the slow onset of symptom relief with antidepressant medications that target serotonin. Antidepressant medications change serotonin levels within hours of being absorbed, yet antidepressant effects take weeks or longer to manifest (Andrade 2010). If increased serotonin was improving a person’s mood, you would expect mood symptoms to improve from the first dose of the medication.

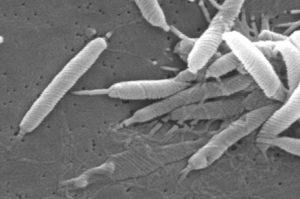

Serotonin Levels

Since 90% of serotonin is manufactured in the gastrointestinal tract and serotonin can not cross the blood brain barrier, blood levels of serotonin are not thought to accurately reflect levels in the brain (Pietraszek 1992). However, studies on the spinal fluid of depressed patients have also looked at levels of serotonin by measuring its breakdown products. A meta-analysis of the research in humans found no correlations with reduced serotonin levels in spinal fluid and depression symptoms (Ogawa 2018). The data strongly suggests that overall serotonin levels are not decreased in the brains of patients with depression.

Serotonin Transporters

Other research has looked at serotonin transporters. Serotonin transporters remove serotonin from the active locations around brain cells, reducing serotonin activity. If people with depression have lower serotonin levels, you would expect serotonin transporter activity to be increased. Yet a meta-analysis of patients with depression found exactly the opposite (Kambeitz 2015).

Oddly, even though we know medications like Prozac block serotonin transporters and decrease their activity, the authors of the study said that their opposing findings confirmed the serotonin hypothesis (Moncrieff 2023).

Serotonin Receptors

Interestingly, studies on serotonin receptors also show the exact opposite of the expected findings from the serotonin hypothesis. While there are numerous types of serotonin receptors, the only one that has been well characterized in humans with depression is known as serotonin receptor 1A. The serotonin 1A receptors inhibit the release of serotonin. Therefore, to have less serotonin, the activity of the receptor should be increased. Yet in cases of depression, a reduction in receptors has been repeatedly found (Wang 2016).

Conclusion

Depression is a complex disease, likely related to multiple components, including inflammation, nutritional status, personal and social history, hormones, toxicity and other components. While the pharmaceutical industry has long tried to boil down depression to a deficiency of serotonin and a few other neurotransmitters, the research does not confirm this overly simplistic hypothesis. While changes in neurotransmitters can affect how we feel, they are likely not the main underlying cause of depression symptoms. It’s well past time to expand our understanding of depression and explore other potential components that contribute to the condition.