Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Can It Be Effectively Diagnosed?

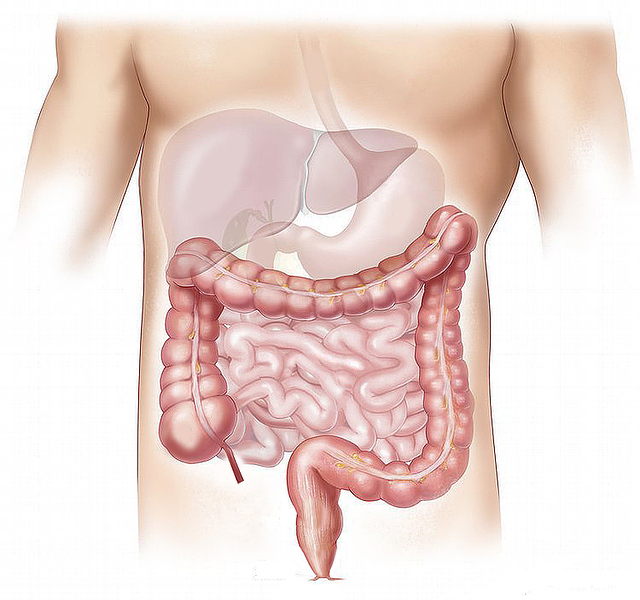

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is defined as an excess of bacteria growing in the small intestine. In healthy individuals, bacterial populations in the small intestine are low. However, for some individuals, the mechanisms that prevent bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine can become compromised. Normally, rhythmic muscle contractions sweep the contents of the small intestine down into the large intestine. If these contractions become dysregulated, it becomes easier for bacteria and other organisms to grow and maintain a larger presence in the small intestine.

When bacteria overgrow in the small intestine, they get access to incoming food before absorption. If the food is high in sugars and starches, the bacteria often produce excessive gas that can cause bloating. In addition, waste products from the bacteria can cause irritation and inflammation in the digestive tract and throughout the body.

SIBO is thought to contribute to many different conditions. It appears likely to play a role in irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, obesity, liver problems, heart failure, blood clots, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, autism, autoimmune conditions, fibromyalgia and dementia (Sroka 2023). Identifying patients struggling with SIBO should be a high priority. As such, it’s worth exploring the different diagnostic tests and their potential reliability.

Diagnostic tests that are often considered to identify SIBO include:

- Breath tests

- Endoscopy with small intestinal sample collection and culture

- Capsule-based testing

- Stool culture

- Urinary bile-acid-conjugate testing

Breath Tests

Probably the most common diagnostic test encountered for SIBO is the breath test. The test includes the consumption of a sugar, like lactulose or glucose, followed by the collection of breath samples over the next few hours. Individuals with intestinal bacterial overgrowth have increased gas production that can be detected in breath.

While the testing is fairly straightforward, it has significant drawbacks. First, patient preparation needs to be adhered to. Patients need to avoid (Rezaie 2017):

- Exercise and smoking the day of the test

- Fermentable foods the day before and the day of testing

- Antimicrobial drugs or antimicrobial herbal protocols for four weeks

- Treatments for constipation or diarrhea for one week prior

- Proton pump inhibitors for heartburn should be discontinued prior to testing

The test has numerous false positives and false negative results, especially in patients that have fast or slow intestinal transit. In these situations, changes in transit time can falsely elevate or reduce gas levels leading to inaccurate results. Low stomach acid levels can also disrupt testing.

For every laboratory test, there is a sensitivity and a specificity. Sensitivity tells you how often to expect a false negative result. Specificity tells you how often to expect a false positive result. Ideally a laboratory test should be 100% sensitive and specific.

Breath testing for SIBO has a sensitivity hovering around 50%. In other words, it misses HALF of people that actually have SIBO. Specificity is somewhat better, at around 75%, meaning that approximately one in four results are falsely positive (Losurdo 2020).

While a lot of doctors rely heavily on breath testing to diagnose SIBO, based on its poor accuracy, its use for diagnostic and treatment purposes should be questioned. Clearly, a more sensitive and specific test is needed for the accurate diagnosis of SIBO.

Endoscopy with Small Intestinal Fluid Aspiration

While some researchers refer to endoscopy with fluid aspiration and culture as the gold standard diagnostic technique for SIBO, others have seriously questioned this title (Lim 2023).

Endoscopy is the process of passing a scope down the throat into the stomach. For a SIBO diagnosis, however, the scope has to pass through the stomach and deep into the small intestine. From there, it gathers a fluid sample, which needs to remain contamination free while the scope is withdrawn. The procedure is expensive, complex and carries significant risks. It’s also not widely available.

One study found that almost 20% of SIBO samples collected by scope were contaminated (Cangemi 2021). This would suggest that one in five results would be false positives from the growth of bacteria that originated from locations other than the small intestine.

Other problems with the technique include the fact that many small intestinal bacteria do not culture on normal culture plates. Therefore, false negative results can also occur due to the presence of bacteria that don’t reliably grow. Estimates suggest that only 20% of bacteria present in the small intestine grow on standard culture plates (Citters 2005). In other words, the vast majority of bacteria that can overgrow in the small intestine will remain undetected on a standard culture.

Based on these numerous deficiencies, endoscopy would also appear to be a poor choice for the diagnosis of SIBO.

Capsule-Based Testing

A non-digestible, lab-in-a-capsule system has been developed to detect SIBO. One system uses a capsule that can be swallowed that includes gas sensors that can measure gas levels directly in the small intestine (Zadeh 2018). A separate group used a similar concept, showing that a capsule is exposed to 3000 times higher gas levels than those found in the breath. The capsule can also determine if the gas is coming from the small intestine, eliminating problems from patients with slow or fast intestinal transit (Berean 2018). While the approach holds promise, more clinical research is needed to determine the safety and efficacy for swallowing SIBO diagnostic capsules.

Stool Culture

Stool culture involves collecting a sample of stool for growth on culture plates. While stool testing can yield some interesting information, it also has significant limitations. The culture results do not indicate where the bacteria came from. For reference, the large intestine contains around then-thousand times more bacteria per gram of dry contents as compared to the small intestine (Berg 1996).

Due to this vast difference, stool cultures more often represent the bacteria present in the large intestine rather than the small intestine. Additionally, as mentioned under small intestinal culture, numerous bacteria found in the stool do not culture on standard culture plates, further complicating stool culture interpretation.

Urinary Bile-Acid-Conjugate Testing

Initial studies have also started to explore urinary testing of specific bile-acid conjugates for the diagnosis of SIBO. The test works by taking a chemical that is attached (conjugated) to a bile acid which can only be separated by intestinal bacteria. The excretion of this marker compound in the urine can then give an estimate of the level of bacteria present in the small intestine.

While animal and human studies have been conducted, the current results are quite limited (Maeda 2023). With the minimal level of evidence available, it is hard to know how effective urinary testing could be for diagnosing SIBO.

Conclusion

The majority of the current testing available for SIBO has major limitations. Standard testing options, including endoscopy with culture and breath testing both have serious drawbacks, including numerous false positive and false negative results. Relying on standard diagnostics to identify cases of SIBO is problematic. While capsule testing may help to improve SIBO diagnostics, more research is needed to establish safety and efficacy before it can generally be recommended. The current diagnostic situation puts patients and providers in a bind, as identifying individuals with SIBO is not straightforward.

While controversial, treatment of potential cases through diet, probiotics and herbal antimicrobials may be a more pragmatic approach with limited risks until better diagnostic tools are more widely available.