Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) Treatment

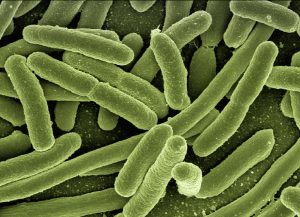

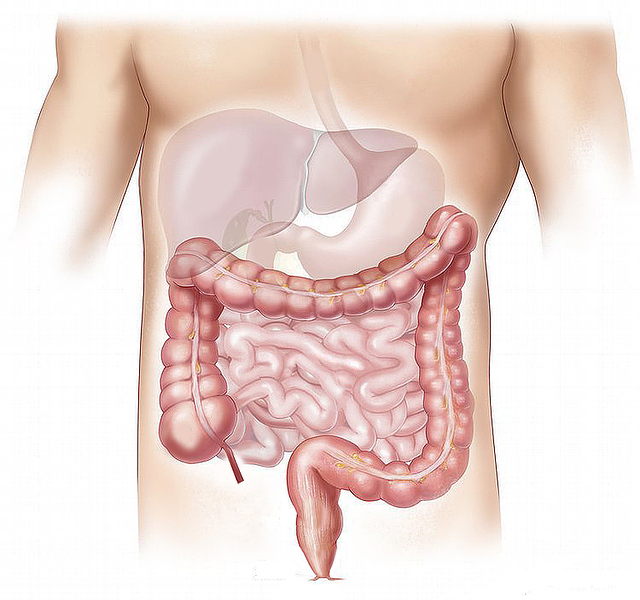

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition where the regulatory mechanisms for slowing bacterial growth in the small intestine have failed. Since the small intestine is dark, warm and repeatedly full of food, it should come as no surprise that bacteria could potentially overgrow.

In a healthy small intestine, rhythmic waves of the smooth muscle lining the intestines sweep bacteria and other contents down into the large intestine. If these rhythmic waves become dysregulated, bacteria can start to overgrow (Bohm 2013). Similarly, if stomach acid levels are reduced, it can be easier for outside bacteria to survive and grow in the small intestine. Medications used for heartburn that block stomach acid increase the risks for SIBO (Su 2018).

While the standard diagnostics for SIBO all have major limitations, the condition is still believed to be quite common. Some estimates suggest that around one-third of patients with gastrointestinal concerns have SIBO (Kiow 2020). And bacterial overgrowth is not benign, as it appears to contribute to numerous disease states, including irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, fatty liver, gallstones, thyroid problems, multiple sclerosis, autism, Parkinson’s disease, fibromyalgia, heart failure and other conditions (Efremova 2023).

Standard SIBO Treatment

The treatment of SIBO is two-fold: reduce the overgrowth of bacteria and restore the mechanisms that prevent bacterial overgrowth from occurring. The mainstream antimicrobial approach is generally the medication rifaximin, a non-absorbed antibiotic that can reduce levels of bacteria throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The efficacy of rifaximin treatment is dose dependent, meaning that higher doses are more effective than lower doses. A recent study concluded that around 60% of patients have at least temporary eradication of bacterial overgrowth with rifaximin treatment (Wang 2021).

After effective antibiotic treatment, a “prokinetic agent” is utilized to stimulate the cleansing muscular waves in the small intestine. Research on prokinetic agents for SIBO is limited and standard drug treatment regimens are not well established. Some prokinetic agents also carry significant risks. Erythromycin and naltrexone, two drugs used in low doses, are often considered as potential prokinetic agents for SIBO treatment (Pimentel 2009, Ploesser 2010).

Integrative Treatment Approaches for SIBO

Dietary Treatments for SIBO

Low FODMAP Diet

Dietary factors can cause or contribute to SIBO. As such, dietary measures are often helpful for treatment. As a general principle, foods that have large quantities of constituents that feed bacteria can worsen SIBO symptoms. A low FODMAP diet can provide a tailored approach by eliminating most bacterial food sources and then slowly reintroducing foods to find the most expansive, yet effective diet for symptom control. As a treatment, low FODMAP diets are most extensively studied for reducing the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. A recent meta-analysis found a low FODMAP diet to ranked higher than any other intervention for its treatment (Black 2022).

While low FODMAP diets can be effective, they are challenging for most patients to implement as they severely limit many food choices. At a minimum, any diet that reduces processed foods and simple sugars is a step in the right direction. Generally, a low FODMAP diet or other healthier eating patterns aren’t fully effective on their own and need to be combined with additional strategies to treat SIBO.

Elemental Diet

While a low FODMAP diet is difficult to implement, an elemental diet is even more challenging. However, as a treatment, unlike a low FODMAP diet, an elemental diet on its own can reverse the condition for a large percentage of patients. Elemental diets treat SIBO by depriving the bacteria in the small intestine of a food source for between two and three weeks. The diet is based on “meals” with all predigested ingredients, typically consumed as a liquid. This allows the nutrients to be absorbed by the first six inches of the small intestine while the rest of the digestive tract remains empty.

An elemental diet consists of amino acids for protein, glucose for carbohydrates, added oils for fat and all the essential vitamins and minerals. Commercial options are available that attempt to improve the flavor, as the ingredients do not taste good on their own. No additional food is allowed during the course of the diet.

From personal experience, I can vouch for the difficulty in following the elemental diet. Not eating any normal food for two weeks can quickly become unpleasant. However, the elemental diet has a remission rate for SIBO of around 85% (Pimentel 2004). For patients with the grit to get through the two to three weeks, it may still be a reasonable option worth considering. As with other treatment approaches, an elemental diet should be overseen by a knowledgeable health care provider.

Natural Antimicrobials

There are numerous natural antimicrobials that can be considered for the treatment of SIBO. However, clinical trials comparing herbal products with antibiotics are very limited. One small trial found herbal antimicrobials to be superior to the antibiotic rifaximin, although they were only effective for just under 50% of patients (Chedid 2014). A case report describes success with enteric coated peppermint for SIBO (Logan 2002), and animal studies also suggest a probiotic-and-essential-oil combination may help with bacterial eradication (Aslan 2023).

For individuals interested in trying natural antimicrobials to treat SIBO, it is highly recommended to work with a knowledgeable health care provider familiar with their use. Natural antimicrobials used in higher doses for treating SIBO often result in side effects that should be monitored carefully.

Probiotics

One of the simpler approaches for treating SIBO involves the addition of probiotic supplements. A meta-analysis from 2017 included 18 studies on probiotics (Zhong 2017). They found that probiotics cleared SIBO in around 60% of cases. Considering the safety of probiotics for individuals with a healthy immune system, they probably should be considered first-line therapy when combined with healthier eating patterns.

Natural Prokinetic Agents

While there are a number of herbs known to stimulate the rhythmic contractions of the intestinal tract, there is no research available on their use specifically for SIBO. Herbs like ginger, caraway and peppermint may have a place as natural prokinetic agents, but more research is needed (Ghayur 2005, Madisch 1999).

Conclusion

SIBO is a challenging condition to effectively identify and treat. And even in cases where the bacteria are initially eliminated, sustained remission is often difficult to achieve. Due to the risks of side effects with antibiotics, natural treatments, including dietary strategies, probiotics, antimicrobial herbs and natural prokinetic agents may be helpful. While the initial data is promising, more research is needed to refine effective protocols.